However, the main objective for this article, is for my personal development, to become whom I want to be.

For trainers, I wish this article will help you in educating your learners.

For learners, I wish this will help you establish the right attitude in training as well as finding a good trainer for yourself.

Titles for Chinese Martial Arts Teacher

Sifu/shifu 师父, literally means teacher+father. Grandmaster = 宗师, Master = 大师, Teacher = 老师, Coach = 教练。Another title that is pronounced exactly the same as sifu is, 师傅, which means Mentor.

There's are titles that Chinese are very familiar with, but could be confusing for people not exposed to the Chinese's culture. Also, there are certain instructors that are very particular about these titles.

Technically speaking, for an individual who has a high level of expertise in his art, the most honorable title one person could give to him would be "Master", "大师”。Titles like Grandmaster 宗师 are of course even more honorable. Not only does it mean that this individual is highly skilled, but it usually means that he also has a huge number of students, and even grand-students. Not many people are able to earn this title, or deserve this title within their lifetime, and those who does are truly commendable. One could address another as master, or grandmaster as a respect for his achievement, but need not necessary a student of this master or grandmaster. Due to the Chinese's virtue of humility, such titles are often conferred, and should never be self-proclaimed.

The title of Sifu 师父, is not a title earned easily. In fact, most Sifu should be 师傅, rather than 师父.

Please understand that, even difference in a single word could have a total different meaning in the Chinese language. Let's break up these 3 syllabus,师,傅,父。

师, generally means specialist in a particular topic, or teacher.

Example, 工程师=Engineer, 医师=Doctor, 设计师=Designer.

老师 is teacher, simply because in ancient times, teacher are usually elders, as 老=Elder, and students do not go to school to study mathematics or science, but simply virtues. Thus, the studied elderly are usually the teachers in the school.

傅,means tutor, or to assist.

父,simply means, father.

Origin of the Title: Sifu 师父

A lot of Master whom made a name for themselves by teaching, or by defeating several opponents on in fights/challenges/ring, were often hired by rich businessmen or officials, to teach martial arts to their sons. The Chinese believe that learning martial arts will instill discipline, perseverance and endurance in their sons, as well as improving their health. Several well known martial artists were actually from wealthy family whom started learning martial arts because of their weak physique when they are young. Very often, such engagement of the master's services was a rather long term, and the Master will be residing within the family's compound, and be paid and have his meals provided by the hirer.

One such example was Grandmaster Liu Yun Qiao whom popularized Ba Ji Quan in Taiwan. As a child, Grandmaster Liu was in very poor health. At the age of five, at the request of his father, he learned Tai Zu Changquan (Emperor's Longfist) from their family bodyguard Zhang Yao Ting in order to help improve his condition. His initial martial arts training was intended to activate improved blood circulation and activate his qi. When Liu was seven, his father hired the Ba Ji Master Li Shu Wen. Well known for his martial arts skills throughout five Northern provinces, he became Liu's personal trainer, living in the Liu estate. For more than ten years Liu was personally trained daily in Li Shu Wen's system of bajiquan, pigua zhang, and liuhe da qiang (six harmony big spear). This provided Liu with a solid foundation in the martial arts which lasted throughout his life.

During the tenure of services, the martial arts master often taught more than just martial arts, and often play an important role in the upbringing of the student, and as the teaching usually begins as a rather young age, it is not uncommon for them to be seen as a fatherly figure in the eyes of the student.

Apart from such engagement, martial arts master would either roam the country seeking for people in need of their services, or start a martial arts school in a town to pass on his arts. A master whom have a school in town was often very well respected in the town, and will be the go to guy if there's dispute, robbers or pirates attack. The master will usually observe, and selectively pick his "in-door" disciples, whom he will passed all, or most of his arts to, and usually along with certain medicine prescription that was passed down to him by his own Sifu. Disciples of this caliber, often end up staying with the master, and are taken care of by the master and his family. Thus, to the student, this master became his martial arts father, thus the term, Sifu 师父. When it reached such stage of learning, most teaching were no longer part of a commercial dealing, but simply like a father to son relationship.

Most people continued the traditional of addressing their martial arts mentor, Sifu 师父 today. Personally I am perfectly alright with this, but as much as it could be just a title, the mentor have deserve this title. For the learner, addressing your mentor as sifu shows the respect you have for him, and for the trainer, to earn this title, you have to work hard to earn it.

Undesirable Traits of a Mentor in Chinese Martial Arts

Chinese martial arts is a complex subject to learn, and even more so to teach. As such, there's a few traits that I have observed from several martial arts instructors that I feel should be corrected.

I am your father sifu

As I mentioned in the above passages, the role of the instructor in Chinese Martial Arts have differed from older times, and as such, titles that address the mentor as a second father is no longer deserving anymore. At least in most part of the world.

There are martial arts teachers out there today that still insist on being address, and even treated as a Sifu/martial arts father. Such individuals often exert their authority by claiming that such respect and authority should be given to them as part of the traditional of Chinese martial arts. However, they do not often treat their students as a son or daughter as part of what the real traditions really mean, and thus, I have my doubt if they should deserve the kind of treatment they desired.

These teachers could be highly competent in their skills, and feel they deserved to be given the fatherly authority and respect due to the commitments they put in to master their skills. Very often, the real reason for them to be holding martial arts classes is not to pass on or spread the arts, but rather to boost their ego and make them feel good about themselves.

Furthermore, the lines between teachers and students are more clearly drawn nowadays. Often, it's simply a commercial transaction. Modern days students treat learning martial arts no different from attending a cooking class, or a tennis lesson. He will pay a school fees for X number of lessons, and have a desired outcome of that particular subject at the end of the course.

Students are more influenced by the western education system and culture nowadays, where respect are given to individuals whom have proven themselves to the student, unlike oriental culture where one must naturally submit to anyone who is more senior in age or status.

Such mentality in teaching generally backfire, as they make students feel uneasy and getting pushed around for reasons they couldn't understand. In my observation, it is very unfortunate if an individual (especially adult learner) meet such teacher as their first Chinese martial arts class. When they leave the class, they typically when dismiss that all Chinese martial arts instructors are like this, and when likely not learn Chinese martial arts again.

Acting Smart

Pretty often, we will see a Grandmaster featured in a Kung Fu movie, say a short Chinese phrase, or do a simple gestures, and while the rest of the people were confused by what the Grandmaster is doing, the lead actor would be enlightened. This has to do with the Chinese's culture again where they believe, 智者不言,言者不智. "The wise will refrain from speaking, the one speaking is not wise." Conservative and traditional Chinese feels that, there's a lot to be learn from the unspoken, and often think that one should teach by hinting, rather than imparting the knowledge directing.

To a certain degree, I am in agreement. For many crafts and arts to be learned, it is true that many people ask too many questions before attempting and practice, and they end up confusing themselves. Say in drawing, one would have to learn to draw a straight line first. Everyone assume they can draw a straight line, but just take a piece of paper and try to draw a straight line without a ruler, can you do it?

Chinese always say, you got to learn to walk before you can learn to run.

However, some instructors don't truly why their teachers only tell them certain martial arts phrases 口诀 at certain time, or do not fully understand such teaching pedagogy, and perhaps their teachers also didn't understand what their teachers are doing. We have to understand that in the conservative Chinese environment, it is often deem to be a rude behavior to question your senior's action. So, they ended up with, monkey see, monkey do, continuing to teach the new generation of students just like how they were taught; except, students in today's time are no longer the way they used to be.

Adult learners nowadays are comparatively more inquisitive when learning, and very goal oriented when learning. In fact, that is how modern education system mould them to be like. Learners are not able to learn blindly if they do not understand the intention behind the practice that they are doing, and even if they do so, they would not be able to last too long if their curiosity is not fulfilled.

The problem with some teachers are, they might have feel that they are smarter than you because he could read out the phrase that you didn't know, or they understand it themselves, so should you. Or, it could be simply the case of, they do not know what it means either. Another problem that we are facing today is, most of these martial arts phrases are written with old Chinese grammar, that sometimes doesn't make sense even if you could read the words.

Teachers have to be a bit more patient with explaining this theories to the learners, and also, only reveal the information at the right time to avoid confusing the learners. Some teachers like to tell all the kung fu phrases to the learners at one go, explain a small part of it, and then dismiss it. I personally do not think it's a right idea, and think it's the teacher's duty and responsibility to understand and explain, verbally or non-verbally any information he would want to disseminate to the students.

Over-Teaching

Another aspect that is often ineffective and harmful to the learners is over-teaching. There are some teachers whom are well versed in various martial arts styles, and seems to be proficient in multiple martial arts forms and style to the unknowing students. As much as one could argue that different martial arts styles share many similarities, but for one to be highly proficient in both theory and martial arts in just a single martial arts style requires a lifelong dedication. Example, Grandmaster Yip Man of the Wing Chun Style, Grandmaster Chen Xiao Wang of the Chen Style Tai Chi, Grandmaster Wong Fei Hung of Hung Gar. All of these Grandmasters became a grandmaster, highly skilled, lots of great students, simply because, they spent their lifetime honing a single craft.

The truth is, despite the similarities among various martial arts, each of the martial arts are able to be known as a particular style is due to each of their unique approach in both training and applications. It would be foolish and shallow to undermine the depth of each martial arts style.

However, it is pretty common for martial arts practitioners to be doing cross training, be it out of curiosity, for complementing what they know, family traditions, or sometimes, just luck of fate. But usually, any highly skilled martial artists are accomplished because of a strong foundations in just 1 or maybe 2 martial arts style. Once they have acquired a strong fundamentals in one style, it usually become easy for them to learn new styles due to their improved body coordination and body efficiency. But when it comes to natural reflex actions, they will still execute their foundation martial arts instinctively until they practice another martial arts hard enough that it became instinct as well.

The problem of over-teaching comes when the teacher have to teach a complete syllabus of a martial arts style that is not his core subject to a new martial arts learner. Usually when the teacher learns the new style, due to fact that he already have a high level of fundamental skills in another arts, he do not learn from the ground up. As such, unless he spend a lot of time thinking about it, he would more likely find it challenging to teach the subject from ground up. The problem with most Chinese teacher is, "face", or simply put, ego. it would damage their ego to admit that they are not familiar with teach the basics of that style, after basic is easy right?

Thus, when being put into such situation, they will often try to supplement what they do not know with either more exercises, or with exercises from other styles and try to convince the learners that all of these skills are the same. Simply state, "If you can't convince, confuse."

Such instructors usually overwhelms their students at the beginning with lots of different exercises and applications, and after a short while, seem to run short of specialized subject to teach. Learners will often feel that they are not learning or improving and give up considering that martial arts is too complex for him.

Master Awesome

Some teachers spend alot of time training talking about the kind of tough exercises they did in their younger days, or how students nowadays are incomparable to those during his time. The subconscious objective of such effort is simply to make themselves feel good by putting his students down. Simply, ego boosting.

Such.types are usually tandem with the "I am your sifu" types as they both seek ego magnification rather than martial arts education.

Such behaviors often discourages students then to motivate them to prove themselves better.

See no touch

One of the most common kind of teaching is what I call the see but no touch teaching. What it means it, whatever martial arts that are being taught, are meant to be performed and display as a form, but not meant for any practical applications. I could be offending many teachers or even martial arts practitioners. But this is something all Chinese martial arts practitioners need to change to lift the reputation of Chinese martial arts.

A lot practitioners, teachers or learners alike are doing Chinese martial arts as a dance performers. Thus, in Europe, people are classifying them as Wushu, and those with practical usage as Kung Fu. But in reality, there should be no such differentiation. The real face of Chinese Martial Arts is fighting and self defense. But take the set routine or application out of the equation is like remove a steering wheel from a car, or blade from a samurai sword.

There are teachers whom teach, and probably also learn that Chinese martial arts is a culture, used to build up discipline, health, and perseverance, and because the modern have no longer any need for martial abilities, we do not have to learn it anymore. If such thoughts were to continue and widespread, Chinese martial arts will evolve to be another dance in 20 years time, and we will definitely lose it culturally.

One of the most common kind of teaching is what I call the see but no touch teaching. What it means it, whatever martial arts that are being taught, are meant to be performed and display as a form, but not meant for any practical applications. I could be offending many teachers or even martial arts practitioners. But this is something all Chinese martial arts practitioners need to change to lift the reputation of Chinese martial arts.

A lot practitioners, teachers or learners alike are doing Chinese martial arts as a dance performers. Thus, in Europe, people are classifying them as Wushu, and those with practical usage as Kung Fu. But in reality, there should be no such differentiation. The real face of Chinese Martial Arts is fighting and self defense. But take the set routine or application out of the equation is like remove a steering wheel from a car, or blade from a samurai sword.

There are teachers whom teach, and probably also learn that Chinese martial arts is a culture, used to build up discipline, health, and perseverance, and because the modern have no longer any need for martial abilities, we do not have to learn it anymore. If such thoughts were to continue and widespread, Chinese martial arts will evolve to be another dance in 20 years time, and we will definitely lose it culturally.

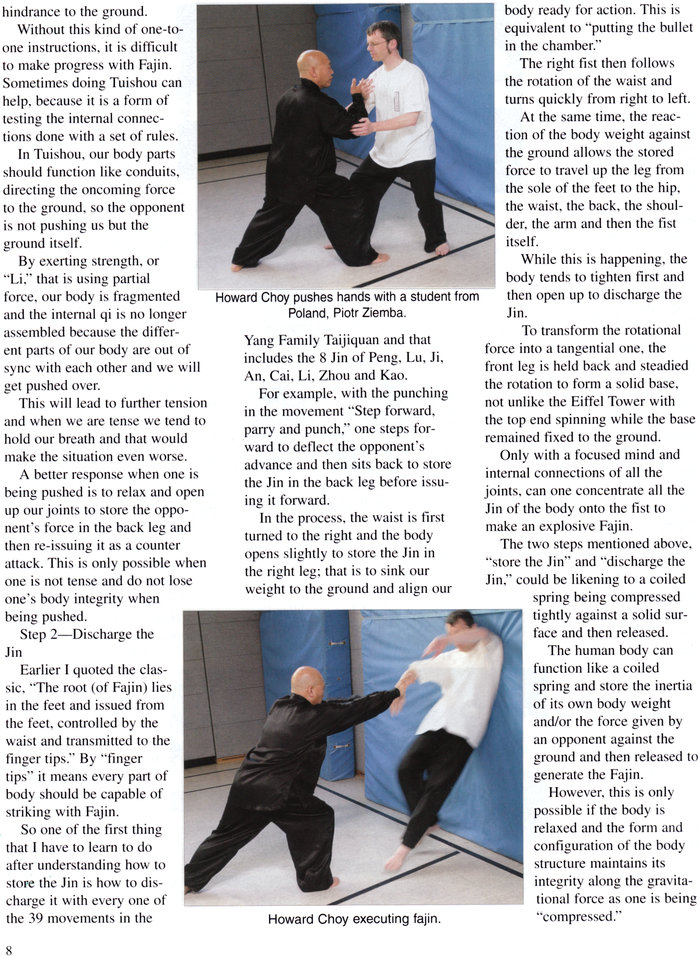

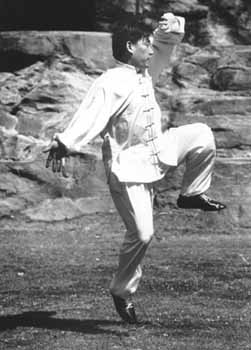

Chen Xiaowang, grandson of the famous Chen Fake, is recognized as the present-day keeper of Chen style taijiquan. In this rare interview, master Chen reveals the true history of his family’s style.

Chen Xiaowang, grandson of the famous Chen Fake, is recognized as the present-day keeper of Chen style taijiquan. In this rare interview, master Chen reveals the true history of his family’s style.