Learning taijiquan is in principle similar to educating oneself; progressing from primary to university level, where one gradually gathers more and more knowledge. Without the foundation from primary and secondary education, one will not be able to follow the courses at university level. To learn taijiquan one has to begin from the elementary and gradually progress to the advanced stage, level by level in a systematic manner. If one goes against this principle thinking he could take a quick way out, he will not succeed. The whole progress of learning taijiquan, from the beginning to achieving success consists of five stages or five levels of martial/combat skill (kung fu). There are objective standards for each level of kung fu. The highest is achieved in the fifth level.

The standard and martial skill requirements for each level of kung fu will be described in the following sections. It is hoped that with these, the many taijiquan enthusiasts all over the world will be able to 'assess' on their own their current level of attainment. They will then know what they need to learn next and advance further step-by-step.

The First Level of Kung Fu

In practising taijiquan, the requirements on the different parts of the body are: keeping a straight body; keeping the head and neck erect with mindfulness at the tip of the head as if one is lightly lifted by a string from above; relaxing the shoulders and sinking the elbows; relaxing the chest and waist letting them sink down; relaxing the crotch and bending the knees. When these requirements are met, one's inner energy will naturally sink down to the dan tian. Beginners may not be able to master all these important points instantly. However, in their practice they must try to be accurate in terms of direction, angle, position, and the movements of hands and legs for each posture. At this stage, one need not place too much emphasis on the requirements for different parts of the body, appropriate simplications are acceptable. For example, for the head and upper body, it is required that the head and neck be kept erect, chest and waist be relaxed downward, but in the first level of kung fu, it will be sufficient just to ensure that one's head and body are kept naturally upright and not leaning forward or backward, to the left or right. This is just like learning calligraphy, at the beginning, one need only to make sure that the strokes are correct. Therefore, when practising taijiquan at the beginning, the body and movements may appear to be stiff; or 'externally solid but internally empty'. One may find oneself doing things like: hard hitting, ramming, sudden uplifting and or sudden collapsing of body or trunk. There may be also be broken or over-exerted force or jin. All these faults are common to beginners. If one is persistent enough and practices seriously everyday, one can normally master the forms within half a year. The inner energy, qi, can gradually be induced to move within the trunk and limbs with refinements in one's movements. One may then achieve the stage of being able to use external movements to channel internal energy'. The first level kung fu thus begins with mastering the postures to gradually being able to detect and understand jin or force.

The martial skill attainable with the first level of kung fu is very limited. This is because at this stage, one's actions are not well coordinated and systematic. The postures may not be correct. Thus the force or jin produced may be stiff, broken, lax or on the other hand too strong. In practicing the routine, one's form may appear hollow or angular. As such one can only feel the internal energy but is not able to channel the energy to every part of the body in one go. Consequently, one is not able to harness the force or jin right from the heels, channel it up the legs, and discharge it through command at the waist. On the contrary , the beginners can only produce broken force that 'surge' from one section to another section of the body. Therefore the first level kung fu is insufficient for martial application purposes. If one were to test one's skill on someone who does not know martial arts, to a certain extent they can remain flexible. They may not have mastered the application but by knowing how to mislead his opponent the student may occasionally be able to throw off his opponent. Even then, he may be unable to maintain his own balance. Such a situation is thus termed "the 10% yin and 90% yang; top heavy staff".

What then exactly is yin and yang? In the context of practising taijiquan, emptiness is Yin, solidity is yang; gentleness or softness is yin, forcefulness or hardness is yang. Yin and yang is the unity of the opposites; either one cannot be left out; yet both can be mutually interchanged and transformed. If we assign a maximum of 100% to measure them, when one in his practice can attain an equal balance of yin and yang, he is said to have achieved 50% yin and 50% yang. This is the highest standard or an indication of success in practicing taijiquan. In the first level of skill in kung fu, it is normal for one to end up with '10% yin and 90% yang'. That is, one's quan or boxing is more hard than soft and there is imbalance in yin and yang. The learner is not able to complement hard with soft and to command the applications with ease. As such, while still at the first level, learners should not be too eager to pursue the application aspect in each posture.

The Second Level of Kung Fu

The level starting from the last stage of the first level when one can feel the movement of internal energy or qi to the early stage of the third level of kung fu is termed as the second level of kung fu. The second level of kung fu involves further reducing shortcomings such as: stiff force/jin produced while practising taijiquan; over- and under-exertion of force as well as movements which are not well coordinated. This is to ensure that the internal energy/qi will move systematically in the body in accordance with the requirements of each movement. Eventually, this should result in smooth flowing of qi in the body and good coordination of internal qi with external movements.

After acquiring the first level of kung fu, one should be able to practise with ease according to the preliminary requirements of the movements. The student is able to feel the movement of internal energy. However, the student may not be able to control the flow of qi in the body. There are two reasons for this: firstly, the student has not mastered accurately the specific requirements on each part of the body and their coordination. As an example, if the chest is relaxed downward too much, the waist and back may not be straight, or if the waist is too relaxed then the chest and rear may protrude. As such, one must further strictly ensure that the requirements on each part of the body should be resolved so that they move in unison. This will enable the whole body to close or unite in a coordinated manner (which means coordinated internal and external closing/union. Internal closing implies coordinated union of heart and mind, of internal energy and force, tendons and bones. External closing/union of movements implies coordinated closing of hands with legs, elbows with knees, shoulders with hips). Simultaneously, there should be an equal and opposite closing movement of another part of the body and vice versa. Opening and closing movements come together and complement each other. Secondly, while practising one may find it hard to control different parts of the body all at once. This means one part of the body may move faster than the rest and result in over-exertion of force; or a certain part may move too slowly or without enough force, thus resulting in a under-exertion of force. These two phenomena both contradict the principle of taijiquan. Every movement in Chen style taijiquan is required not to deviate from the principle of the 'spiralling silk force' or chan-si jin. According to the Theory of Taijiquan, 'the chan-si-jin originates from the kidneys and at all times is found in every part of the body'. In the process of learning taijiquan, the spiralling-silk method of movement (ie. the twining and spiralling method of movement) and the spiralling-silk force (ie. the inner force produced from the spiralling-silk method of movement), can be strictly mastered through relaxing shoulders and elbows, chest and waist as well as crotch and knees and using the waist as a pivot to move every part of the body. Starting with rotating the hands anti-clockwise, the hands should lead the elbows which in turn leads the shoulders which then guide the waist (the part of the waist corresponding to that side of the should that is being moved. In actual fact the waist is still the pivot). On the other hand, if the hands rotate in a clockwise direction, the waist should move the shoulders, the shoulders move the elbows, the elbows in turn move the hands. For the upper half of the body, the wrists and arms should appear to be gyrating; whereas for the lower portion of the body the ankle and the thigh should appear to be rotating; as for the trunk, the waist and the back should appear to be turning. Combining the movements of the three parts of the body we should visualise a curve rotating in space. This curve originates from the legs, with the centre at the waist and ends at the fingers. In practising the quan, (or the form), if one feels awkward with a particular movement, one can adjust one's waist and thigh according to the sequence of flow of the chan-si-jin to achieve coordination. In this way, any error can be corrected. Therefore, while paying attention to the requirement on each part of the body to achieve total co-ordination of the whole body, the mastering of the rhythm of movement of the spiralling-silk method and spiralling silk force is a way of resolving conflicts and self-correction for any mistake in practising taijiquan after attaining the second level of kung fu.

In the first level of kung fu, one begins with learning the forms, and when one is familiar with the forms, the student can feel the movement of internal energy in the body. The student may well be very excited and thus never feel tired or bored. However, in entering the second level of kung fu, the student may feel there is nothing new to learn and at the same time misunderstand certain important points. The student may not have mastered these main points accurately and thus find that their movements are awkward. Or, on the other hand, the student may find that he or she can practise the quan smoothly and express force with much vigour but cannot apply them while doing push-hands. Because of this, one may soon feel bored, lose confidence and may give up altogether. The only way to reach the stage where one can: produce the right amount of force, not too hard and not too soft; can change actions at will; and can turn smoothly with ease, is to be persistent and strictly adhere to principles. One has to train hard in the form so that the body movements are well co-ordinated, and with 'one single movement can activate movements in every part of the body' , thus establishing a complete system of movements. There is a common saying, 'if the principle is not clearly understood, consult a teacher; if the way is not clearly visible, seek the help of friends'. When the principles as well as the methods are clearly understood, with constant practice, success will prevail eventually. The Taijiquan Classics state that, 'everybody can possess the ultimate, if only one works hard.' And 'if only one persists, ultimately one should achieve sudden break through'. Generally, most people can attain the second level of kung fu in about four years. When one reaches the state of being able to experience a smooth flow of qi in the body, one would suddenly understand it (the command of qi) all. When this happens, one would be full of confidence and enthusiasm as one goes on practising. One may even have the strong urge to go on and on and wouldn't feel like stopping!

At the beginning of the second level kung fu the martial art skill attained is about the same as in the first level kung fu. It is not sufficient for actual application. At the end of the second level kung fu one is nearing attaining the third level kung fu, as such the martial skill acquired may be applicable to a certain extent.

The next section introduces the martial skill that should be attainable half-way through the second level kung fu (so are the third, fourth and fifth levels of kung fu in the subsequent sections. They are discussed with reference to the skill attainable in the half-way stage in each level.)

Push-hands and practising taijiquan are inseparable. Whatever shortcomings one has in his quan form will show up as weaknesses during push-hands and thus giving the opponent an opportunity to take advantage of them. Because of this, in practising taijiquan every part of one's body must be well coordinated with the rest, there shouldn't be any unnecessary movement. Push-hands requires warding-off, grabbing, squeezing and pressing to be carried out so precisely, so that the upper and lower bodies move in co-ordination and it is thus difficult for opponents to attack[. As the saying goes: 'No matter how great is the force on me, I should mobilise four ounces of strength to deflect one thousand pounds of force'. The second level of kung fu aims at achieving smooth flowing of qi in the body by correcting the postures so as to reach the stage when qi should penetrate the whole body passing through every joint as if it (qi) is sequentially linked. However, the process of adjusting the postures involves making unnecessary or unco-ordinated movements. Therefore, at this stage, one is unable to apply the martial skill at will during push-hands. The opponent will concentrate on looking for these weaknesses or he or she may win by surprising one into committing all the errors like over-exerting, collapsing, throwing-off and confronting of force. During push-hands, the opponent's advance will not allow one to have time to adjust one's movements. The opponent will make use of one's weak point to attack so that one will lose balance or will be forced to step back to ward off the advancing force. Nevertheless, if the opponent advances with less force and in a slower manner, there may be time or opportunity to make adjustments and one may be able to ward off the attack in a more satisfactory manner. Drawing from the above discussion, for the second level kung fu, whether one is attacking or blocking-off an attack, much effort is needed. Very often, it will be an advantage to make the first move, the one who moves last will be at an disadvantage. At this level, one is unable to 'forget' oneself but 'play along with' the opponent (ie. not to attack but to yield to the opponent's movement); unable to grasp an opportunity to respond to change. One may be able to move and ward off an attack but may easily commit errors like throwing-off or collapsing and over-exerting or confronting [the?] force. Because of these, during push-hands, one cannot move according to the sequence of warding-off, grabbing, pressing and pushing down. A person with this level of skill is described as '20% yin, 80% yang: an undisciplined new hand.'

The Third Level Kung Fu

'If you wish to do well in your quan (or form), you must practice to make your circle smaller.' The steps in practising Chen-style taijiquan involve progressing from mastering big circle to medium circle and from medium circle to small circle. The word 'circle' here does not mean the path/trail resulting from movements of the limbs but rather the smooth flowing of the internal energy of qi. In this respect, the third level kung fu is a stage in which one shall begin with big circle and end with medium circle (in the circulation of qi).

The Tiajiquan Classic mentioned that 'yi and qi are more superior than the forms' meaning that while practising taijiquan one should place emphasis on using yi (consciousness). In the first level of kung fu, one's mind and concentration are mainly on learning and mastering of the external forms of taijiquan. While in the second level of kung fu, one should concentrate on detecting conflicts/unco-ordination of limbs and body and of internal and external movements. One should adjust body and forms to ensure a smooth flow of the internal energy. When progressing into the third level kung fu, one should already have the internal energy flowing smoothly: what is required is yi and not brute force. The movements should be light but not 'floating', heavy but not clumsy. This implies that the movements should appear to be soft but the internal force is actually strong/sturdy, or there is strong force implied in the soft movements, and the whole body should be well-coordinated and there should not be any irregular movements. However, one should not just pay attention to the movement of qi in the body and neglect the external actions. Otherwise, one would appear to be in a daze and as a result, the flow of internal qi may not only be obstructed but may be dispersed. Therefore, as stated in the Taijiquan Classics, 'attention should be on the spirit and not just qi, with too much emphasis on qi there will be stagnation (of qi)'.

One may have mastered the external forms between the first and second level kung fu, but he may not have attained co-ordination of the external with internal movements. Sometimes, due to stiffness or stagnation of the actions, full breathing-in is not possible. On the other hand, without proper co-ordination of the internal and external movements, it is not possible to empty one's breath completely. Thus, when practising quan one should breath[e] naturally. After entering into the third level kung fu, there is better co-ordination of internal and external movements. As such generally the actions can be synchronized with breathing quite precisely. However, it is necessary to consciously synchronize breathing with movements for some finer, more complicated and swifter actions. This is to further ensure co-ordination of breathing and actions so that it gradually comes on naturally.

The third level of kung fu basically involves mastering the internal and external requirements of Chen-style taijiquan and rhythm of exercise as well as the ability to correct oneself. One should also be able to command the actions with more ease and should also ha[ve] more internal energy (qi). At this level, it is necessary to further understand the combat skill implicit in each quan form and its application. For this, one has to practise push-hands, check on the forms, the quality and quantity of the internal force and expression of the force as well as dissolving of force. If one's quan form can withstand confrontational push-hands then one must have mastered the important points of the form. He would gain more confidence if he continues to work hard. He may then step up his exercise routine and add in some complementary practice like practising with the long staff, sword or broad sword; spear and pole as well as practising fa jin i.e. expression of explosive force on its own. With two years continuous practise in this manner, generally one should be able to attain the fourth level of kung fu.

With the third level of kung fu, although there is smooth flow of internal qi and the actions are better coordinated, but the internal qi is weaker and the coordination between muscle movements and the functioning of the internal organs is not sufficiently established. While practising alone without external disturbances, one may be able to achieve internal and external coordination. During confrontational push-hand[s] and combat, if the advancing force is softer and slower, one may be able to go along with the attacker and change one's actions accordingly; grab any opportunity to lead the opponent into a disadvantageous situation[; or] avoid the opponent's firm move but attack when there is any weakness, manoeuvring with ease. However, once encountering a stronger opponent, the student may feel that his peng jin, i.e. blocking force, is insufficient, and there is a feeling that one's form is being pressed and about to collapse (this may destroy the unfailing position which is supposed to be never-leaning and never-declining but with all round support), and cannot manoeuvre at will. The student may not achieve what the Taijiquan Classics describe as 'striking with the hands without them being seen, once they are visible, it is impossible to manipulate'. Even in leading-in and expelling-out the opponent, one [may] feel stiff and much effort is required. As such the skill at this stage is described as '30% yin, 70% yang, still on the hard side.'

The Fourth Level Kung Fu

Progressing from the stage with medium circle to that with small circle is required of the fourth level kung fu. This is the stage nearing success and thus is of high level of kung fu. One should have mastered the effective method of training, be able to grasp the important points in the movements; be able to understand the martial/combat skill implicit in each movement; to have smooth flow of the internal energy or qi; and the co-ordination of actions with breathing. However, during practice, each step and each movement of hands should be carried out with a confronting opponent in mind, that is to say, one has to assume that he is surrounded by enemies. For each posture and each form, each part of the body must move in a linked and continuous manner so that the whole body moves in unison. 'Movements of the upper and lower body are related and there should be a continuous flow of qi with the control being at the waist.' So that when practising quan, one should carry it out 'as if there is an opponent although no-one is around'. When actually confronted, one should be brave but cautious, behaving 'as if there is no-one around though there is someone there.'

The training content (like quan and weapons) is similar to that in third level of kung fu. With perseverance, generally the fifth level kung fu can be reached in three years. In terms of martial skill the fourth level differs much from the third level kung fu. The third level kung fu aims at dissolving the opponent's force and to get[ting] rid of conflicts in one's own actions. This is to enable oneself to play the active role and forcing the opponent to be passive. The fourth level kung fu enables one to dissolve as well as express force. This is because at that level, one would have sufficient internal jin, flexible change in yi and qi and a consolidated system of the body movements. As such, during push-hands, the opponent's attack does not pose a big threat. On contact with the opponent, one can immediately change one's action and thus disolve the on-coming force with ease, exhibiting the special characteristics of going along with the movements of the opponent but yet changing one's own actions all the time to counteract the opponent's action, exerting the right force, adjusting internally, predicting the opponent's intention, subduing one's own actions, expressing precise force and hitting the target accurately. Therefore, a person attaining this level of kung fu is described as '40% yin, 60% yang; akin to a good practitioner.'

The Fifth Level Kung Fu

The fifth level kung fu is the stage in which one moves from commanding small circle to commanding invisible circle, from mastering the form to executing the form invisibly. According to the Taijiquan Classics, 'with the continuous smooth flowing of qi, with the cosmic qi moving one's natural internal qi, moving from a fixed form to invisibility, one realises how wonderful nature is.' At the fifth level, the actions should be flexible and smooth, and there should be sufficient internal jin. However, it is still necessary to strive for the best. There is the need to work hard day by day until the body is very flexible and adaptable to multi-faceted changes. There should be changes internally alternating between the substantial and insubstantial but these should be invisible externally. Only until then that the fifth level kung fu is achieved.

As regarding the martial skill, at this level the gang (hard) should complement the rou (soft), it (the form) should be relaxed, dynamic, springy and lively. Every move and every motionless instant is in accordance with taiji principle, as are the movements of the whole body. This means that every part of the body should be very sensitive and quick to react when the need arises. So much so that every part of the body can act as a fist to attack whenever is in contact with the opponent's body. There should also be constant interchange between expressing and conserving of force and the stance should be firm as though supported from all sides.

Therefore the description for this level of kung fu is that it is the 'only one that plays with 50% yin and 50% yang, without any bias towards yin or yang, and the person who can do this is termed a good master. A good master makes every move according to the taiji principles which demands that every move be invisible.'

After completing the fifth level kung fu a strong relationship has been established between the co-ordination of the mind, contraction and relaxation of the muscles, movements of the muscles and functioning of the internal organs. Even when encountering a sudden attack such co-ordination will not be hampered as one should be flexible to change. Even then, one should continue to pursue further so as to achieve greater heights.

Development in science is beyond boundary, so is practising taijiquan: one could never exhaust all its beauty and benefits in one's life time.

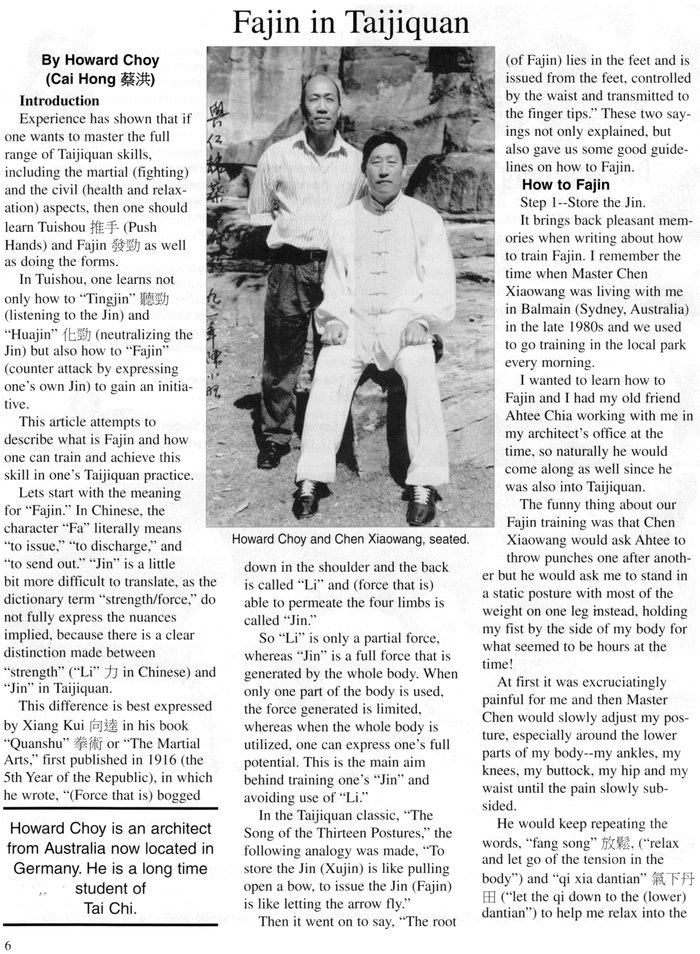

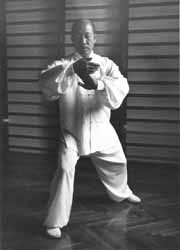

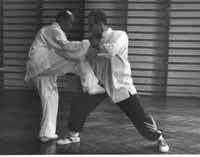

Chen Xiaowang, grandson of the famous Chen Fake, is recognized as the present-day keeper of Chen style taijiquan. In this rare interview, master Chen reveals the true history of his family’s style.

Chen Xiaowang, grandson of the famous Chen Fake, is recognized as the present-day keeper of Chen style taijiquan. In this rare interview, master Chen reveals the true history of his family’s style.